China’s fine traditional culture, extensive and profound, is the crystallization of Chinese civilization’s wisdom, and also an important embodiment of the Chinese people’s cosmology, worldview, social outlook, and moral outlook. The cosmological idea of “the unity of heaven and man,” as Mencius said, “flowing together with heaven and earth,” has been the understanding of the universe held by the Chinese people over thousands of years, and also the methodological approach for the Chinese people to establish themselves and live their lives.

French Sinologist Thierry Meynard, Professor of Philosophy at Sun Yat-sen University and Deputy Director of the Documentation Center for the History of Western Learning Spreading to the East, said that there is much room for dialogue between Chinese traditional cosmology and Western cosmology, as both fundamentally concern how to understand the relationship between the One and the Many. The Chinese cosmology, which emphasises “the unity of heaven and man,” focuses on how differentiation arises under unity; the Western cosmology that asserts “God is fundamentally different from human beings” seeks how unity might be achieved under distinction. In today’s world, facing threats such as climate change and nuclear proliferation, the profound philosophy within Chinese and Western cosmologies can inspire humanity to transcend narrow perspectives, set aside short-term interests, and work together for the future of humankind.

You have conducted extensive and in-depth research on Chinese philosophy. In your view, what kind of cosmology is embodied in China’s fine traditional culture?

Westerners often reduce Chinese philosophy to Confucian ethics represented by the “Three Cardinal Guides and Five Constant Virtues,” and tend to evaluate it as a repressive form of ethics, particularly for women. But this risks overlooking the unique Chinese cosmology, in which individuals actually enjoy vast freedom to move within the boundless universe.

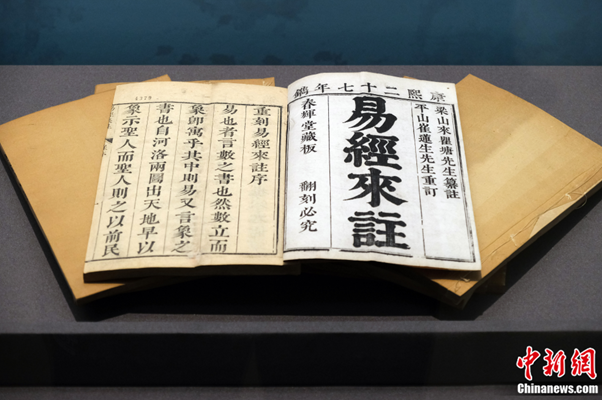

From a philosophical perspective, China’s cosmology originates in the Yijing, developed through a long period including the Pre-Qin and Han periods, and reached more systematic philosophical expression in Song-dynasty Confucianism. Human ethical relations were placed within a broader natural context, connected with seasonal cycles and celestial changes.

In the 16th century, Western missionaries held that the Greek theory of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire) had true scientific validity and used it to dismiss China’s traditional “Wuxing” (五行, metal, wood, water, fire, earth). Yet from the perspective of modern science, neither the four elements nor the Wuxing has empirical grounding. The value of Chinese cosmology lies in its macro perspective, observing interconnections among all things and forming a symbolic system in which individuals can locate themselves and achieve self-understanding.

How does the Chinese cosmology represented by the “unity of heaven and man” differ from or resemble Western cosmology?

In Chinese thought, the “unity of heaven and man” is taken as a self-evident premise. On this basis, one may further discuss how heaven and man have distinct roles and obligations. By contrast, Western thought begins with the essential difference between God and man: God is the master of man. Therefore, humans must respect God’s sovereignty and transcendence. If a person offends God, it is the greatest sin. On the premise that there is an essential difference between God and human beings, Western philosophers and theologians have sought ways for humans to relate to God, to enable understanding between the two, so that humans can act in accordance with God’s will and ultimately achieve union with Him.

Thus, Chinese cosmology focuses on differentiation under unity, while Western cosmology concerns unity under distinction. Although the approaches seem opposite, the fundamental problem is the same: how to understand the relationship between the “One” and the “Many”. Even if the Chinese path emphasises the One and the Western path emphasises the Many, these are differences of approach rather than essential distinctions.

You have pointed out that Aristotelian metaphysical creationism shares much dialogue space with Chinese traditional cosmology. Could you elaborate?

First, we must distinguish between temporal and metaphysical theories of creation.

Due to the influence of the Bible’s “Genesis”, temporal creationism dominated in the West, focusing on clearly separating the Creator from created beings, establishing the distance between God and man. We can observe that the entire biblical narrative explores how humans might bridge this distance and ultimately unite with God.

However, Thomas Aquinas, a representative figure of Scholastic philosophy, building on Aristotle, developed a different view: metaphysical creationism. In his view, philosophy need not assume that God created the universe at a certain moment in time. Instead, the relationship between God and the universe should be understood as a timeless metaphysical relation: the whole universe and all beings exist by directly depending on God. In other words, God is the foundation of all things, not only creating but continuously sustaining them at every moment. This is quite close to Chinese cosmology, which affirms a pre-existing harmony and then proceeds from a generative first principle toward differentiation.

“Huan You Quan”(寰有诠), published in 1628, can be seen as a collision of Song Ming Neo-Confucianism and Scholasticism. How does this commentary on Aristotle’s On the Heavens reflect the convergence of Western and Chinese cosmologies?

Missionaries in late Ming China primarily introduced temporal creationism, presenting it as the core of Western thought, showcasing the distinctiveness of Christianity, and suggesting it could fill a supposed gap in Chinese thought. Yet at the time, Chinese intellectuals were not inclined to accept a view that posited an absolute gulf between Creator and creation.

In 1628, Portuguese Jesuit Francisco Furtado and Chinese scholar Li Zhizao co-authored and published “Huan You Quan” in Hangzhou, aiming to reconcile Aquinas’ metaphysical cosmology with Neo-Confucian cosmology. The book detailed the metaphysical structure of the universe, affirming both the materiality of all beings and the idea that each has its own essence traceable to the supreme essence — God. Here, God is not identical to the God of Genesis, but a more philosophical God. Though the book did not explicitly mention the Neo-Confucian concept of the “Taiji” (太极), this metaphysical creationism demonstrated that the God as metaphysical foundation of all beings was quite similar to the Taiji of the Song Confucians.

Unfortunately, no one pursued this line of convergence after the book’s publication. It was not until 1711, in Philosophica Sinica, that the Belgian Jesuit François Noël directly affirmed the concept of Taiji of the Song Confucians.

From the perspectives of physical relations, ethical order, and cosmological origins, what modern significance do Chinese and Western cosmologies hold?

First, let’s consider physical relations. Today, it is easier to recognize the advantages of Chinese cosmology. Pre-Socratic natural philosophy shared a similar feature, both emphasizing the universe’s continuous wholeness. Aristotle, however, “mistakenly” divided the cosmos into the sublunar and superlunar realms. He believed in an eternal, unchanging aether in the superlunar, distinct from the four natural elements (earth, water, air, fire) in the sublunar. This severed the continuity of cosmic matter.

Until the 16th century, Aristotelian cosmology dominated the West. Later, with Galileo’s astronomical discoveries and Newton’s law of universal gravitation, Western cosmology reaccepted the continuity of cosmic matter. Despite its errors and conjectures, Aristotle’s insight lay in opposing the idea of Earth as a closed system, instead situating it within a web of interactions at the center. Modern astrochemistry, in some sense, confirms this view: the Earth’s origin and evolution must be understood from a cosmic macro perspective.

Second, regarding ethical order: Aristotle argued in On the Heavens that the cosmos operates in a state of harmony without force or violence. In other words, cosmic perfection is equivalent to ethical value. The relations within the universe are not merely physical but also ethical. “Huan You Quan” explained this idea by quoting from the Yijing, “Heaven bestows and Earth brings forth; its benefits know no bounds,” and described humans as microcosms (what Li Zhizao called “small heavens and earth”). This reflected Renaissance humanism: not only is man within the cosmos, but the cosmos is also within man.

Lastly, on cosmological origins: Aristotle did not directly discuss this in On the Heavens, but in Metaphysics he provided a metaphysical foundation for the cosmos. Based on this, Aquinas argued that God and all beings share “existence.” “Huan You Quan” translated this concept into the Chinese word “有” (being), to show that the shared basis of “万有” “寰有” (all beings) lies in God’s “初有” (first being) and “妙有” (mysterious being). By emphasizing the concept of “有”, the book enabled Christian creationism to converge with Chinese thought.

Today humanity faces immense risks and challenges — climate change, nuclear proliferation, and more — all stemming from our failure to situate ourselves within the cosmos and to think holistically about the relationship between humans and the universe. In this respect, traditional Chinese and Western cosmologies offer profound inspiration. Only by recognizing that humanity depends on the cosmos for existence can we transcend narrow perspectives, set aside short-term interests, and work together for the future of humankind.

If you like this article, why not read: How Can Chinese Animation “Go Global”?