How has Sinology developed in Europe? What are the core topics that European scholars focus on? What kind of mainstream “understanding of China” has taken shape? And what efforts should Europe and China make to enhance mutual understanding? Centering on these questions, Professor Helwig Schmidt-Glintzer, a leading German Sinologist, granted an exclusive interview.

What is the general developmental course of Sinological research in Europe?

It is a long and complex story. At first, European missionaries, merchants, and others showed an interest in China. Different European countries developed such interest at different times, with the earliest traces dating back to the 15th century—a period before the modern notion of the nation-state had taken shape. As France and Britain gradually embarked on the path of global expansion, they naturally sought to better understand China. For this reason, what we may now call Sinology emerged earlier in France than elsewhere in Europe.

In Germany, the development of Sinology came relatively later. Initially part of Oriental Studies, Sinology did not become an independent academic discipline until the early 20th century. Before that, most scholars working on China were Orientalists who studied multiple languages. For instance, Otto Franke—one of the pioneers of German Sinology—was originally a specialist in Indian languages and culture before turning his focus to Chinese studies. In this sense, the rise of Sinological research in Europe was closely tied to the formation of European nation-states and to the era of European global expansion.

What is the current state of Sinological research in Germany? What is its position and representativeness within Europe?

German Sinology has developed in parallel with China’s own transformation. Today, while some German Sinologists still study subjects such as oracle bone inscriptions, Han dynasty history, and Song dynasty cultural history, there is a growing number who focus on contemporary China—particularly issues in the social sciences and cultural studies. These researchers are professionals who pay attention to academic developments not only in Europe and the United States, but also in China itself. In this sense, German Sinology is both part of global Sinology and an integral component of European—and specifically Western European—Sinology, thus occupying an important position.

One notable phenomenon is that many German Sinologists publish in English rather than German. This creates a certain problem, since the general German public tends to engage only with easily accessible information in their own language. Fortunately, there are now also excellent works written in German that help introduce China and its diversity to broader German audiences.

What are the core topics of Sinology that Europe focuses on? And what kind of mainstream “understanding of China” has been formed?

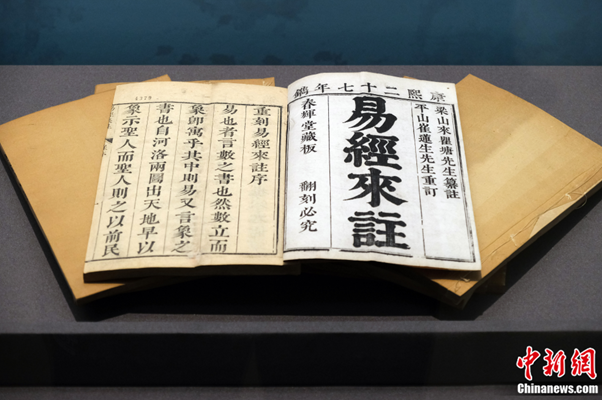

At present, many European scholars devote themselves to studying China’s diversity—its Buddhism, natural sciences, history, and more. At the same time, however, there is a growing trend of viewing China through a more critical lens.

From the origins of European Sinology, Europeans have been studying Chinese thought and political transformation. In the early 20th century, Otto Franke published a book titled Ostasiatische Neubildungen (New Developments in East Asia), in which he analyzed the processes by which East Asian countries began to modernize and change. This process is still ongoing today. To understand it properly, one must study the people of East Asia and their ideas—and that is precisely the work of Sinology. Unfortunately, relevant research has decreased in recent years. Yet this is somewhat understandable, for social research is always complex, no matter where it is conducted.

As for Europe’s “understanding of China,” there are diverse positions. Today, as before, some wish to continue trade with China, while others fear that China’s low-cost goods might undermine the European market—hence the current discussions about imposing additional tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. I believe such debates are normal, but they also carry a danger: that the will to pursue confrontation might become stronger than the will to pursue mutual understanding.

It seems that in Western media and political circles—including Germany—China is almost always discussed from a “critical perspective.” What are the reasons for this? And what constructive attitudes should Europe and China adopt toward each other?

One-sidedness has existed throughout history. But careful observation reveals that the two sides actually share more commonalities than differences—that is my experience. For those who have never been to China, however, the situation may be different: they usually rely on media reports, which tend to be highly one-sided.

Among Chinese studies scholars, different stances always exist, and these inevitably affect academic work. Politics, too, attempts to exert influence over scholarship. Some current debates in Germany—for instance, about China’s growing capabilities—are closely linked to such political dynamics. Political actors often wish to shape a certain image of China, treating it primarily as a threat. I believe this perspective is misguided, but it remains prevalent today.

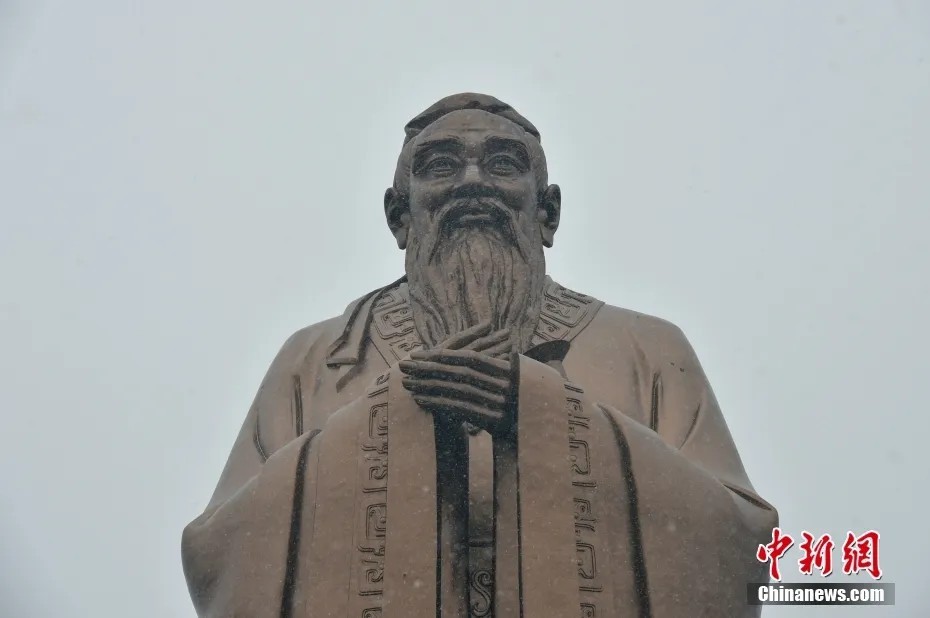

In China, some scholars of German literature may be able to read Hölderlin or Schiller, but they may not be familiar with Kang Youwei, Tan Sitong, Confucius, Mozi, or Zhuangzi. Conversely, in Germany, there are Sinologists deeply versed in Chinese sources who may know little about Hegel, Hölderlin, or even Marx. Neither situation is ideal. When I speak as a European, I must take my historical context into account. And in today’s world of multiple conflicts, we need to adopt a truly plural perspective.

In China, there are German literature scholars who can read Hölderlin or Schiller but may know little about Kang Youwei, Tan Sitong, Confucius, Mozi, or Zhuangzi. Conversely, in Germany, there are Sinologists focused on China who know little about Hegel, Hölderlin, or even Marx. Neither situation is ideal. As a European, when I discuss such issues, I must take my own historical context into account. Moreover, in today’s world, conflicts abound between different nations and regions. Faced with such complexity, a multi-perspective approach is essential.

What are the factors affecting mutual understanding between Europe and China? What efforts should be made on both sides?

The factors are closely linked to the positions of each side. For a long time, Europeans were content to see China as a low-cost producer. But suddenly, China began to innovate and manufacture electric vehicles superior to those of other countries. Europeans then realized: “We are no longer the major exporter—China is.” Some Europeans therefore see China’s transformation as a threat.

In reality, however, this is something to be welcomed. Europe and China face common challenges in the process of modernization, such as water resources, air quality, and climate change. Now that China has become more modern, many demand that it conserve resources, among other things. Such expectations are partly reasonable, but also partly driven by the fact that certain political parties in Western Europe have made China into an election issue. Being critical of China wins them voter support, but it also distorts perceptions and undermines objectivity. This is a trend I have observed.

China has already done much to promote mutual understanding. Many Chinese go abroad, learn foreign languages, and speak German, English, French, or Italian. Yet Europeans do not learn Chinese to the same degree. This imbalance needs to be addressed—we need more people studying Chinese.

Both Europe and China must also broaden their horizons. There are many issues to discuss, and both sides have their taboos. If each can maintain some distance from its own entrenched positions, matters could become simpler. China is seeking its own path to modernization. For us, this is an excellent opportunity to observe with curiosity and reflect.

It would be almost impossible—and indeed troubling—to expect all countries to become like the United States, France, or Germany. For a global population of 8 billion, we must recognize the necessity of finding new ways of life, new forms of social organization, new methods of conflict resolution, and new strategies to confront climate change. We must find new paths—and it is most welcome that China is charting one of its own.

If you like this article, why not read: How Has China Achieved Such Substantial Progress in Ecological Civilisation?