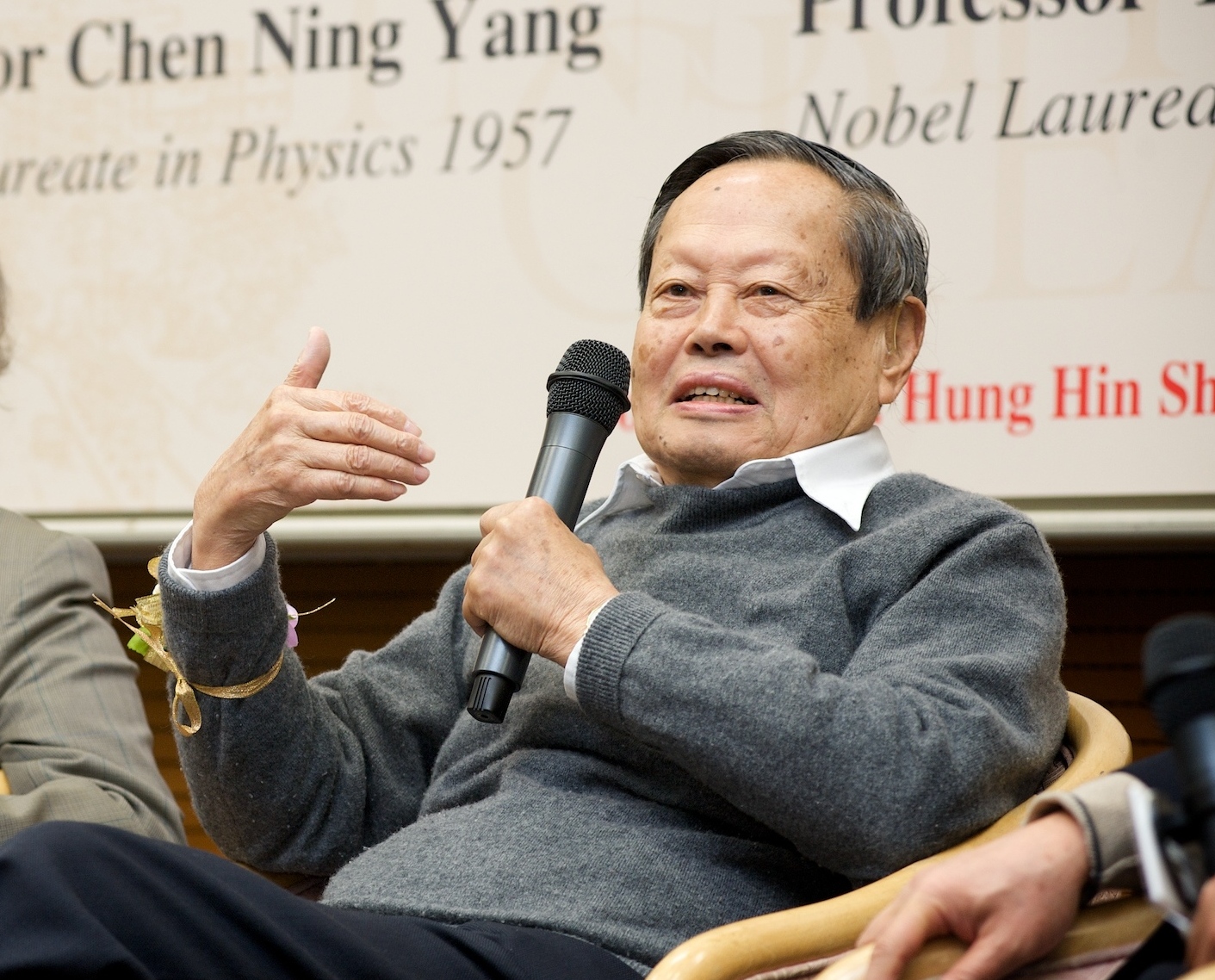

This is a tribute to Nobel laureate Yang Chen-Ning — a physicist who bridged East and West, united science and spirit, and inspired generations across a century.

Yang Chen-Ning, one of the most influential physicists of the 20th century and the first Chinese scientist to win a Nobel Prize, has died in Beijing at the age of 103.

His life traced a remarkable arc through science and history — from war-torn China to the universities of America, and finally back to Tsinghua University in Beijing, where he spent his later years teaching and mentoring young scholars.

Roots of a Scientist

Yang was born in Hefei, China’s eastern Anhui Province, in 1922. His father, Yang Wu-Chih, was a mathematics professor at Tsinghua University. The young Yang grew up on the Tsinghua campus, immersed in books and ideas that would shape his future.

After the outbreak of war in 1937, his family fled to Kunming. There, Yang entered the National Southwest Associated University — a wartime union of China’s top universities. His classmate, the translator Xu Yuanchong, later recalled that Yang was the best student in the university. He excelled in physics and mathematics, graduating with top marks in 1942.

Yang went on to earn his master’s degree from Tsinghua and, in 1945, received a scholarship to study in the United States. At the University of Chicago, he studied under the eminent physicist Edward Teller and earned his PhD in 1948. The following year, he joined the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he would begin a brilliant scientific career.

Yang married his first wife, Chih Li Tu, in 1950, with whom he had three children.

A Revolution in Physics

In 1957, Yang and fellow theoretical physicist Lee Tsung-Dao were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their parity violation theory. The finding overturned one of physics’ long-held assumptions and reshaped our understanding of nature’s laws.. The Nobel committee praised “their penetrating investigation… which has led to important discoveries regarding the elementary particles”.

Yang’s later work continued to influence the very structure of modern physics. The Yang–Mills theory, developed with Robert Mills, became a cornerstone of the Standard Model, which describes how elementary particles interact. His research also advanced statistical mechanics, condensed matter physics, and mathematical physics, leaving a lasting imprint across disciplines.

His contributions placed him in the lineage of thinkers who, like Newton, Maxwell, and Dirac, redefined how humanity sees the natural world.

A Mind Bridging Science and Beauty

Beyond his technical achievements, Yang’s scientific journey was guided by a profound sense of the aesthetic of thought.

In his essay collection, he reflected on the British physicist Paul Dirac, whose ideas, Yang wrote, were “unlike anyone else’s, yet irresistibly captivating.” He described Dirac’s writings as “clear as autumn water, unstained by dust,” with not a trace of waste. Following Dirac’s reasoning, he said, always felt wondrous, leading to insights no one could have imagined beforehand. To Yang, the Dirac equation was nothing short of a revelation—an expression of both scientific rigour and poetic beauty.

This deep appreciation for the beauty and wonder of science would continue to shape his approach when he returned to China, guiding not only his research but also his teaching and mentorship.

A Return to Tsinghua

After decades in the United States, Yang began visiting China more frequently in the 1990s. In 1999, he accepted a professorship at Tsinghua University, where he helped establish the Institute for Advanced Study and raised funds to support young scientists.

Even in his eighties and nineties, Yang continued to teach undergraduates and take part in research. Colleagues remember his authority and deep curiosity. He believed education was not only about passing on knowledge, but about inspiring wonder — the same sense of wonder that had driven his own life’s work.

In 2015, Yang renounced his U.S. citizenship and became an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Six years later, he donated more than 2,000 books, manuscripts, and personal items to Tsinghua University, establishing the Yang Chen-Ning Archive Room.

On October 19, a professor from the Chinese University of Hong Kong laid a bouquet of white chrysanthemums before Yang’s photograph in the memorial room at Tsinghua. He bowed deeply and said he had worked with Professor Yang more than two decades ago. “Professor Yang was not only a world-renowned scholar, but also a kind and gentle elder,” he recalled.

He remembered once inviting Yang to give a lecture on science and philosophy: “Professor Yang readily agreed. His quick mind, the clarity of his reasoning, and the depth of his reflections from that day remain vivid in my memory.”

A Philosopher in the Lab

Beyond his teaching and research, Yang’s curiosity was deeply philosophical, shaping not only his approach to science but his view of life itself.

Physicist Enrico Fermi once said of Yang Chen-Ning, “He was not searching for answers—he was chasing the universe itself.” That pursuit defined Yang’s century-long journey through science — a restless curiosity guided not only by intellect, but by wonder.

On his 100th birthday in 2023, Yang delivered what would become his final public lecture. “Scientific exploration,” he said, “is like searching for a key in the dark. What matters most is believing that the key exists.”

After a lifetime spent probing the mysteries of the universe, he spoke with quiet humility: “From the perspective of the vast cosmos, human life is not of great importance — and the life of an individual, even less so.”

Those words reflected the clarity of a scientist and the serenity of a philosopher — a man who had spent a century seeking truth, only to find wonder.

A Legacy Written in the Stars

Yang Chen-Ning’s century-long life spanned wars, revolutions, and the scientific transformations of the modern age. He was elected to academies across the world, including the Royal Society, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and the Russian Academy of Sciences, and received dozens of international honours. A minor planet discovered by Chinese astronomers was named Yangchenning Star in his honour.

He often quoted the poet T.S. Eliot, whose words captured the symmetry between science and existence that defined Yang’s life:

“In my beginning is my end…in my end is my beginning.”

A life devoted to truth, beauty, and the unity of knowledge had come full circle.

Written by Chen Wang, additional reporting by CNS.

If you liked this article, why not read: Between Myth and Reality: A Nobel Winner’s Odyssey in China