In a land ravaged by war, one young Englishman decided not to watch from the sidelines—but to stand alongside the suffering and build a future from the ruins.

“What I wanted was to live among the people themselves, to see what the war was doing to their daily lives.” These words, written by George Hogg in the foreword to I See a New China, capture the spirit that shaped his short but extraordinary life.

From Oxford to inland China

Born in 1915 in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, Hogg was educated at St George’s School and later at Wadham College, Oxford. There, he persuaded his parents to support a journey that took him across the United States, and on to Japan and China, accompanied by his aunt, the renowned pacifist campaigner Muriel Lester.

Hogg arrived in Shanghai in early 1938. He had intended only a brief visit. But after witnessing the suffering caused by the Japanese invasion, he decided to stay. Refusing to be a passive observer, he travelled to inland China and began working with Rewi Alley, a New Zealand-born activist. Together, they joined the Gung Ho cooperative movement. Hogg’s mission was clear: to support China’s resistance through education, industrial self-reliance, and the care of children orphaned by war.

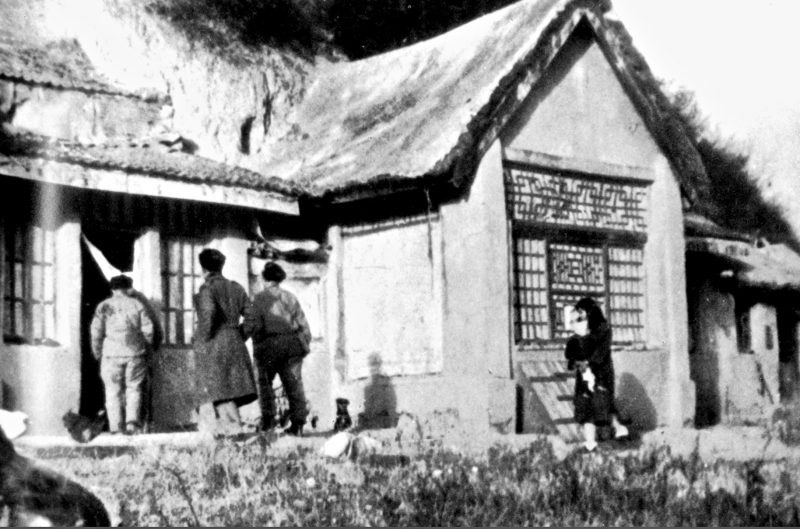

In 1942, with Alley’s backing, Hogg became headmaster of the Bailie School in Shuangshipu, Feng County, Shaanxi. The school faced acute hardship. Hogg frequently cycled across treacherous mountain roads to the Gung Ho office in Baoji to appeal for emergency funds. Despite these difficulties, he adopted four war orphans and treated all the boys as family.

He lived in a modest cave-dwelling near the school. In winter, he mended students’ clothing by hand and shared what little food he had with those in need. He taught English, music, and sport, often playing basketball or singing with the boys.

A Journey of Courage

In late 1944, as the Nationalist Army began conscripting schoolboys, Hogg took a courageous step: he led 60 boys on a perilous 700-mile journey to Shandan, in Gansu Province. There, he converted abandoned temples into classrooms and workshops, secured food and supplies, and gave the boys practical training and joy—teaching them farming, singing, hiking, and sport. “We are raising students who can drive a tractor and read Shakespeare,” he once said.

In July 1945, Hogg stubbed his toe while playing basketball. The injury became infected with tetanus. Two of his boys undertook a motorcycle journey to Lanzhou for medicine, only to find that time had already run out. Hogg died three days later, aged just 30. As he slipped away, the boys sang to him—songs he had taught them himself.

He was buried just outside Shandan. His gravestone bears lines from his favourite poem:

“And Life is colour and warmth and light, And a striving ever more for these. And he is dead who will not fight, And who dies fighting has increase.”

A month later, the war ended. But the legacy of George Hogg lives on—in the lives he touched, in the school he helped build, and in his quiet courage and compassion.

Written by Estelle Tang, additional reporting by CNS, Gansu Online (GSCN), Gungho.org.cn, chinaflagnet.com.

If you liked this article, why not read Weihsien: A WWII Camp, an Olympic Hero, and a Legacy of Peace