In a quiet village in the southern Belgian province of Namur, architect Nicolas Godelet sits in his studio, intent on his drawing. This is the village where he spent his childhood and where he still lives with his family and parents.

Working and living in his hometown, Nicolas Godelet doesn’t seem to have travelled far, but the media articles displayed at the door of his studio suggest the contrary- and without exception, these articles featuring him or reporting on him have to do with China.

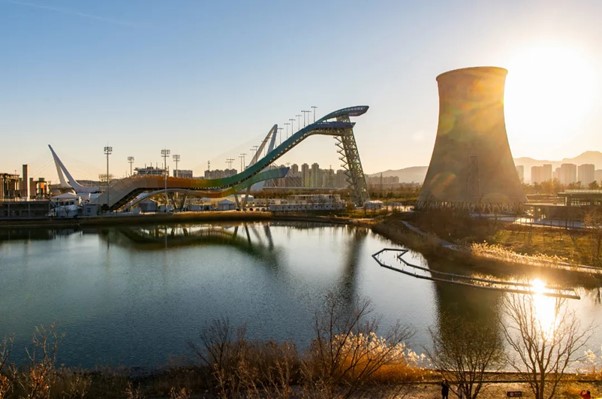

A master of Chinese architectural culture and a fluent Chinese speaker, he has been involved in the design of the Shougang Ski Jump at the Beijing Winter Olympics, the urban planning of the ancient city of Pingyao in Shanxi Province, the Belgian Pavilion at the World Horticultural Expo in Beijing, and the new building of the Belgian Embassy in Beijing. In the Belgian architectural world, Godelet is a true ‘China expert’. In 2024, the renovation of the China House in Brussels, which had been closed for more than 10 years, was launched, and he was once again involved.

Recently, the reporter of East Meets West went to Namur to interview Nicolas Godelet, exploring his journey to China and his Chinese story.

Nicolas Godelet, a Belgian architect, has been living and working in China for many years. He is well versed in Chinese architectural culture and has been involved in the design of the Shougang Ski Jump for the Beijing Winter Olympics, the Ancient City of Pingyao in Shanxi Province, the Belgian Pavilion at the World Horticultural Expo in Beijing, and the new building of the Belgian Embassy in China. With the concept of sustainable architecture, he is committed to promoting exchanges and co-operation between Belgium and China in the fields of architecture, bridges, landscape design and urban planning.

You often refer to yourself as a child of the mountains and an architect from the forest, can you talk about your personal experience?

I grew up right outside the studio compound, surrounded by fields, forests, valleys and rivers. At one point as a child, I felt unlucky because I didn’t have fashionable clothes to wear, I didn’t go to the cinema very often, and my cultural life wasn’t as rich as it could have been compared to the kids in the city.

But looking back, nature has given me many gifts. For example, when I played in the forest, I built a ‘tree house’ with my friends, and I saw many houses and bridges made of local stones, which made me interested in architecture.

At the age of 15, with a backpack, I started travelling on my own, which was arguably the biggest change in my life, because suddenly I felt that borders could be crossed and that there was really no difference between people. 17 years old, I went to India and explored the Himalayas, and a year later I came back to Belgium and enrolled at the University of Louvain-la-Neuve, where I studied Architecture.

Why did you become interested in China?

I have looked out over China from the Himalayan border region of India, but I can say that I didn’t know much about China because at that time there was very little news coverage of China in Europe, and limited exposure to Chinese people in my daily life.

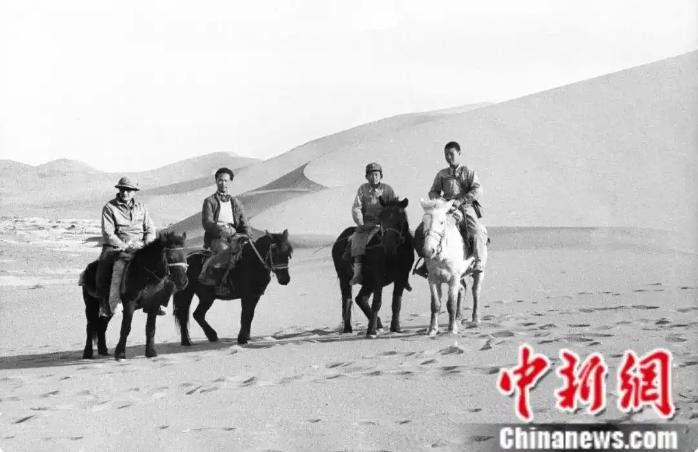

I first came to China in 1996 because I saw pictures of the landscape of Kashgar in Xinjiang in a magazine, and thought that Kashgar was very remote and rich in cultural heritage, and was eager to see this ancient city on the Silk Road, so I bought a ticket to fly to Beijing first, and then bounced all the way to Kashgar.

This trip changed my impression of China. Originally, I thought that Chinese people wore grey clothes, they were very serious, and China was similar to other Asian countries, but it turned out not to be true. China is different, the wide grassland and vast land made me think that China is beautiful.

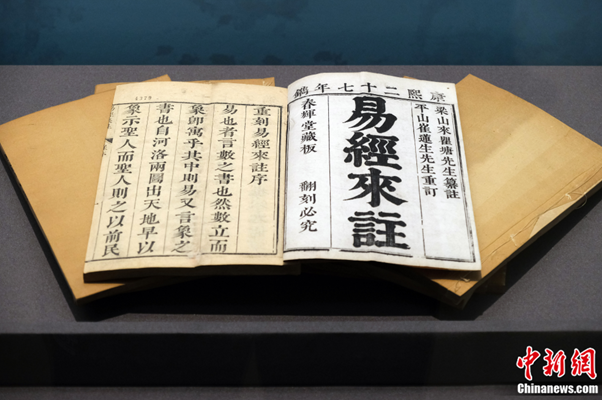

After returning to Belgium, I took courses in Chinese and Oriental scripts at university, focusing on oracle bones and the Phoenician alphabet, in the hope of discovering a link between hieroglyphic forms of writing and the art of architecture. 2002 saw me move again to Beijing, first to study abroad and later to set up an architectural studio.

You have participated in the design of a series of high-profile architectural projects such as the Shougang Ski Jump for the Beijing Winter Olympics, the city planning of Pingyao Ancient City in Shanxi Province, and the new building of the Belgian Embassy in Beijing, etc. What is your experience of the exchange and co-operation between Eastern and Western architectural cultures?

Compared to Belgium, China has more opportunities to design large-scale architectural projects, such as the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, which can fulfil an architect’s ambitions, especially for young architects.

I love Chinese culture and believe that architectural projects must respect local culture, rather than copying foreign designs and turning buildings into ‘amusement parks’, which is probably one of the reasons why I was involved in the urban planning of the Ancient City of Pingyao in Shanxi Province. When I was involved in the design of the Shougang Ski Jump for the Beijing Winter Olympics, I drew on the experience of transforming old industrial areas in Germany and emphasised the importance of not ‘tearing down and building up’, but rather of establishing the concepts of transformation, symbiosis with nature and recycling, as well as taking into account both environmental protection and economic benefits.

During my time in Beijing, I was sometimes a ‘bridge’. For example, during the construction of the National Theatre of China, I was the interpreter for Paul Andreu (the French architect who designed the National Theatre of China). He was very anxious because other people didn’t understand architectural terms such as columns and welding, but he and I both spoke French and were both architects, so communication was much smoother.

You study the connection between oracle bones and the art of architecture, and back then you put your Beijing studio in a courtyard house. What is your understanding of Chinese architectural culture?

Chinese architectural culture has ‘feng shui’, tell you can not just build a house, we must first analyse the environment, study the sun, and prevent wind. Space design should pay attention to the comfort, privacy, security, etc. From the architect’s point of view, ‘feng shui’ contains certain scientific concepts, reflecting the ‘unity of man and the world’ philosophy.

There is also the common mortise and tenon structure of ancient Chinese architecture. European architecture is common triangular structure, is not deformable, but in the mortise and tenon structure, there are gaps, and is deformable. Once an earthquake occurs, the building can go through these deformations to absorb the impact caused by earthquakes, in favour of the building anti-seismic. Mortise and tenon craftsmanship has been passed down from generation to generation in China and can be said to be unique.

Nowadays, Belgian architectural culture emphasises green energy, recycling and sustainability. For example, I was involved in the design of the new building of the Belgian Embassy in China, which uses wooden structure technology – that can be considered ‘outdated’ by many people, but wooden structure buildings are actually very low-carbon and environmentally friendly. We also broke up the bricks removed from the old building and made them into new bricks for the walls of the new building, reflecting the concept of recycling.

Each country has its own architectural traditions and styles, but we can look for the ‘common ground’ at the spiritual level, such as ‘adapting to local conditions’, ‘using local materials’, ‘low-carbon and energy-saving’, etc. Through scientific design and in-depth study of the rational use of resources, we can achieve interactive symbiosis among people, nature and architecture.

If you liked this article why not read: East Meets West丨Wang Jie, What is the significance of the successful UNESCO heritage application for the Spring Festival?