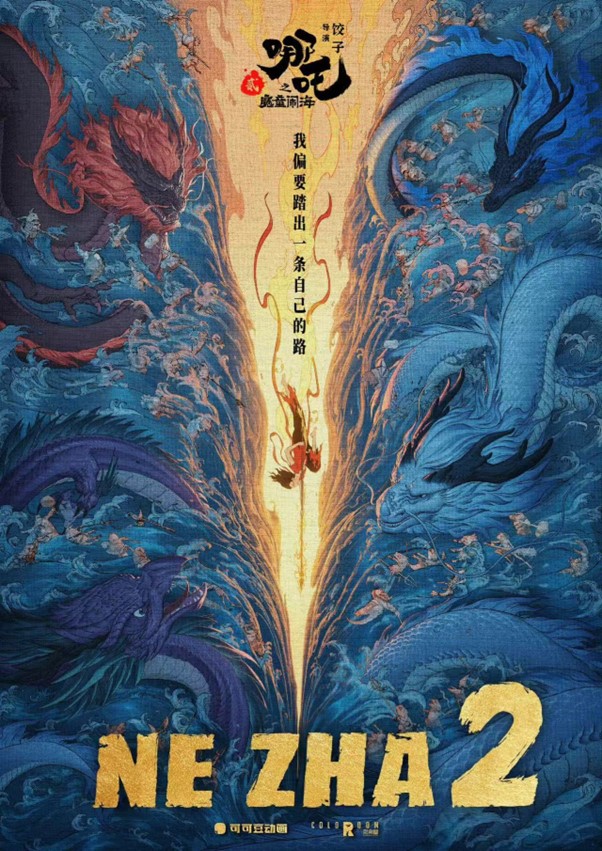

“I am determined to forge my own path.” Recently, the Chinese animated film Nezha 2 was officially released in overseas cinemas, with this line featured on its international poster.

This path is the result of a decade of dedication from Nezha 2’s director, Yang Yu (known as “Jiaozi”)—a path of “exchanging heart for heart.” It is a groundbreaking journey where ancient Eastern myths have been creatively deconstructed and reimagined, becoming a phenomenal crossover success. It also marks the path of Chinese animation over the past century—from closely mirroring global standards to ultimately rediscovering its own identity.

From Medical Student to Anime Creator

In 1942, Princess Iron Fan, produced by China’s Wan Brothers and featuring a rich Chinese classical painting style, was screened in Japan. Inspired by Disney’s Snow White, this animated film became the first feature-length animated film in Asia and the fourth in the world. A young Japanese viewer was deeply impressed after watching it and became fascinated with the art of animation.

“At the time, Disney’s Snow White had just been released, yet China had already produced Princess Iron Fan with such diverse special effects — it was truly astonishing.” Ten years later, in 1952, this young man, named Osamu Tezuka, abandoned his medical career to pursue a career in art. Inspired by Sun Wukong, he created manga such as Astro Boy. He reflected on this experience in the postscript of one of his manga.

On the last day of 2008, the animated short film See Through made a striking debut in mainland China. Its director, Jiaozi, was also a young man who abandoned a medical career to pursue a path in animation.

Jiaozi’s university classmate Wang Hongwei recalled that Jiaozi had just entered the West China College of Pharmacy of Sichuan University when he was a good drawer, and had been in charge of the college’s board newspaper for a long time. In his third year of college, he suddenly fell in love with 3D animation design, and could render on the computer for three days in a row without interruption in order to have a shot of more than ten seconds.

After graduating from West China College of Pharmacy of Sichuan University, Jiaozi worked in an advertising agency for a short period of time before quitting his job to stay at home and devote himself to animation with the support of his mother.

See Through is only 16 minutes long, but it represents three years and eight months of Jiaozi’s dedication and effort. In the end, the short film swept over 30 awards both domestically and internationally.

At the end of this short film, the 28-year-old director included a long list of acknowledgements to honour his predecessors. The list featured Disney, the Wan Brothers, and Osamu Tezuka.

In 2015, Monkey King: Hero is Back, directed by Tian Xiaopeng, surpassed the Hollywood film Kung Fu Panda 2 to become the highest-grossing animated film in the Chinese market at the time, holding the record for several years. That same year, Jiaozi began working on the first Nezha movie.

Chinese animation has experienced both glorious heights and deep downturns. The box office failures of numerous Chinese animated films caused investors to lose confidence in the industry. Before the release of Monkey King: Hero is Back, most Chinese animated productions survived by keeping production costs within the limits of government subsidies. As a result, creators were forced to focus on cutting costs rather than improving quality.

“Monkey King: Hero is Back was a wake-up call for me. As long as you exchange heart for heart, the audience will respond to quality work — they may even be more forgiving. This strengthened my belief.” After the release of Nezha 1, Jiaozi shared his creative inspiration in an article. He wrote, “Without Monkey King, there would be no Nezha.”

In Jiaozi’s view, the reason for choosing Nezha as the protagonist was to inspire those pursuing their dreams — to offer them encouragement, hope, warmth, and strength. In fact, Nezha represents a reflection of each of us: even when the sky comes crashing down and bends our heads, we can still struggle to grow three heads and six arms to hold up the sky.

The script took two years to refine, going through a total of 66 revisions; production lasted nearly three years, involving over 5,000 initial design shots and more than 1,400 visual effects shots. After relentless effort from Jiaozi and his team, Nezha 1 was finally released to audiences in 2019.

Although the unconventional “dark-eyed Nezha” featured in the initial Nezha 1 posters sparked some scepticism, audiences were soon moved by Nezha’s unique yet deeply human portrayal after watching the film. The movie went on to gross over 5 billion RMB with 140 million viewers, a record that remained unbroken for five years — until it was surpassed by Nezha 2.

Some say that many animation studios took on work for Nezha 1 at a loss. This was confirmed in an article by Jiaozi, where he wrote: “During those years, Chinese animation was in a very weak position. The entire industry was holding back a fierce determination — desperate to create a great work at any cost. Everyone was driven by a shared desire to prove themselves: to ‘break stereotypes and change fate’ — to shatter the audience’s preconceived notions about Chinese animation.”

The Armor of Ten Thousand Dragons in Chinese Animation

“All the dragons have given you their hardest scales. This Armor of Ten Thousand Dragons is indestructible — it’s all up to you now!” In Nezha 1, all the dragons gave their hardest scales to their hope, Ao Bing.

And this time, the Chinese animation industry has given its “hardest scales” to Nezha 2 — and to Jiaozi, the dreamer whose hair turned grey in just five years of relentless pursuit.

Nezha 2 contains more visual effects shots than the total number of shots in Nezha 1, and the number of characters is three times greater than in the first film. Jiaozi initially sought help from top international visual effects teams for some key scenes, but the outsourced results were disappointing. In the end, it was 138 Chinese animation studios that came together to lift this film to become the highest-grossing film in Chinese box office history.

At the time, the Nezha 2 project resembled an “Olympic Village”, attracting the best animation talent from across China. By confronting these challenges head-on, Chinese animators pushed their creative boundaries further than ever before, elevating the technical standards of Chinese animation to a whole new level.

Liang Yi, a professor at the School of Film and Animation at Chengdu University, led a team that contributed to the modeling and scene effects for Nezha 2. In an interview with East Meets West, Liang Yi mentioned that even when the team had already created impressive work, Jiaozi would still encourage them to push further if there was room for improvement. As Jiaozi put it, “Creating something entirely new that no one has ever seen before should be the goal for every director and creator.”

Jiaozi also stated that for Chinese culture to reach a global audience, the key lies in the work itself—in the script, story, characters, and other core elements. “These are not things that can be outsourced.”

On February 13, the mischievous, dark-eyed three-year-old boy made his official debut in overseas cinemas. Nezha 2 exceeded expectations with its popularity and positive reception in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. As of midnight on February 14, the film’s rating on the international review site IMDb had risen to 8.3. By 1:00 PM on February 15, Nezha 2’s global box office had surpassed $1.519 billion.

The New York Times reported that Nezha 2 demonstrates that Chinese cinema is now telling its own stories, rather than relying on Western film companies to produce films based on Chinese folklore.

Although Jiaozi has become the top-grossing Chinese director with the success of the two Nezha films, he remains remarkably low-key. When he occasionally appears in public, he is often seen wearing the same plain sweater from three years ago.

In a widely circulated short video, one of Jiaozi’s rare “high-profile” moments came when a host asked him, “Besides Nezha, which other animated films do you like?” Jiaozi rattled off the answer like listing dishes on a menu: “The entire Shanghai Animation Film Studio collection, the entire Hayao Miyazaki collection, the entire Mamoru Oshii collection, the entire Katsuhiro Otomo collection, the entire Pixar collection, the entire Disney collection,” before grinning and asking slyly, “Shall I keep going?”

It took Jiaozi five years to create Nezha 2 after Nezha 1. During these five years, Chinese animation did not simply wait for another phenomenal hit to emerge. Instead, a wave of remarkable works like I Am What I Am, Chang’an, and Jiang Ziya bloomed across the industry.

According to Cai Shangwei, Director of the Cultural Industry Research Center at Sichuan University, a common thread among China’s outstanding animated films in recent years is their deep exploration of narrative-rich and visually expressive elements rooted in traditional Chinese culture.

Li Xiang, an associate professor at the Sichuan University School of Art, similarly believes that the West has created influential IPs like Marvel and Harry Potter, whose stories, values, and aesthetics have shaped generations. Now that Nezha has taken the global stage, it proves the extraordinary appeal of Chinese stories and the storytelling talent of Chinese creators.

In 1926, during a time of turmoil for the Chinese nation, the Wan Brothers converted an old camera into a film camera in a small room in Shanghai. After experiencing hundreds of failures, they finally created China’s first true animated film, Uproar in the Studio.

As pioneers of Chinese animation, Wan Guchan, one of the Wan Brothers, wrote in Casual Talk on Cartoons, “For Chinese animation to possess boundless vitality, it must take root in the soil of our own national traditions.”

Now, Nezha 2, rooted in Chinese mythology, is telling China’s story to the world — supported by the collective strength of the entire Chinese animation industry.

This is the path of Chinese animation.