Follow Tohinali Tusunali as he carries his grandfather’s legacy, singing the Kyrgyz Manas epic and keeping this heritage alive for future generations.

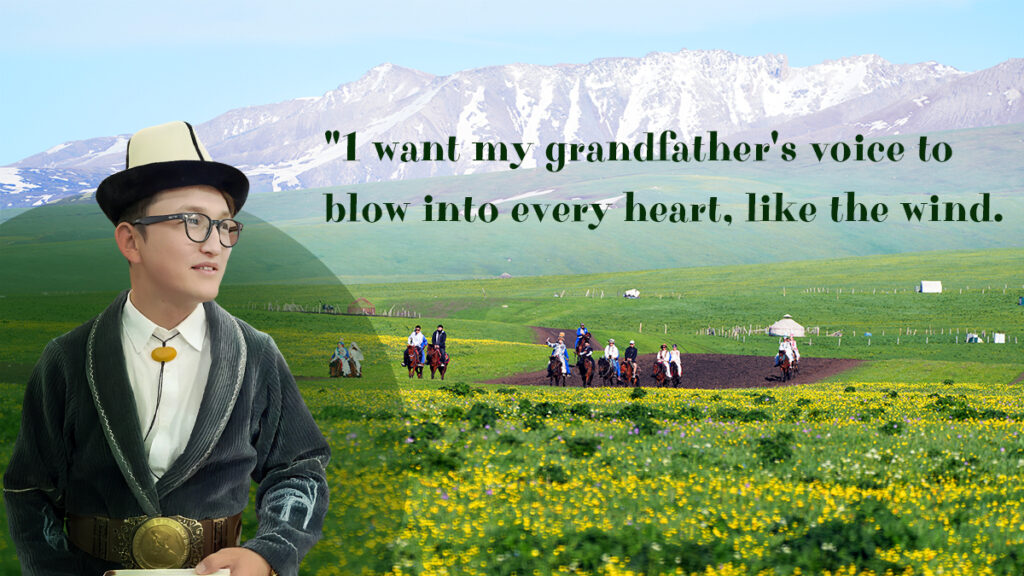

“I want my grandfather’s voice to blow into every heart, like the wind,” says 31-year-old Tohinali Tusunali (托合那力·吐逊那力). His words carry both love and responsibility. As a manaschi, he is a bard responsible for singing and guarding the Kyrgyz epic Manas, one of the world’s greatest living oral traditions.

The Manas epic has been performed for more than a thousand years. It is mainly told among the Kyrgyz people of Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture in Xinjiang, China. The story is long and complex: over 900,000 lines, more than ten times longer than Homer’s epics. To sing all eight parts takes more than a year. The Manas epic tells of Manas, his descendants, and their struggles to defend their homeland. The tales describe courage, sacrifice, and unity. They celebrate not only the Kyrgyz people but also the friendship of many groups who fought together.

A Legacy in the Family

Tohinali’s great-grandfather, Jusup Mamay, was the most famous manaschi of the last century. He was the only person who knew to perform all eight parts in full, an achievement that earned him deep respect.

For Tohinali, the tradition began in childhood. “I fell asleep to the melodies of the epic when I was three years old,” he recalls. “At eight, I started to learn the songs more seriously. My great-grandfather’s yurt was my first classroom. I could not understand all the words, but the rhythm already lived inside me.” Today, he can sing for more than eight hours without stopping.

Manas has always been passed down by voice. Each singer memorises long passages, but also adds their own interpretation. This makes every performance unique. The same story may sound different when told by another singer. Tohinali admits that this beauty also brings challenges. Oral tradition depends on memory, skill, and inspiration. Without new generations, the chain could break.

Innovation Brings New Energy

While oral performance is traditionally the way manas has been preserved, this is now changing.

Scholars are playing a role in keeping the epic alive. At Shihezi University, researchers study Manas and translate it into other languages. Professor Ma Rui, one of the translators, says, “Students from many ethnic groups now join in learning the epic. If you love it, you can learn it.” In recent years, singers have also added instruments such as the guitar, mixing them with traditional Kyrgz instruments like the komuz or flute. Performances now appear not only in village gatherings, but also on large festival stages and even online platforms. Tohinali himself enjoys this blend. “We respect tradition, but we also want young people to feel the rhythm in new ways,” he explains. His concerts show how an ancient story can speak to modern audiences.

Despite these changes to the oral tradition of manas, the spirit of the epic continues. For listeners, Manas is more than a cultural relic. It is a story about love for one’s home and hope for the future. It inspires pride and belonging.

When Tohinali sings, he carries not only the sound of his ancestors but also the dreams of a new generation. From the quiet space of a yurt to the bright lights of a concert hall, Manas continues to echo. It reminds the world that oral tradition still breathes, and that culture lives through the voices of those who choose to keep singing. As tradition changes with the times, Tohinali can bring his great-grandfather’s voice into every heart.

Written by Chen Wang, picture designed by Di Wang, additional reporting by Min Wang, Minna Tian.

If you liked this article, why not read: From Desert Oases to World Stage: The Twelve Muqam, A Cultural Treasure in Xinjiang