British scientist Joseph Needham’s journey across wartime China reveals the resilience of Chinese scientists under extreme hardship.

From 1943 to 1946, British scientist Joseph Needham travelled across China. He visited more than 300 universities, research institutes, and industrial facilities. With his camera and pen, he captured the determination of Chinese scientists during the darkest years of the war against Japan.

Liu Xiao, a visiting scholar at the Needham Research Institute at Cambridge, says Needham first came to China with sympathy and a desire to help. But what he saw changed him. Even in the face of extreme hardship, Chinese scientists and educators demonstrated a fierce will and high morale. His feelings shifted from sympathy to deep respect, and he became a committed supporter of the Chinese people.

Science Under Siege

In February 1943, after months of preparation, Needham arrived in Kunming in Yunnan province, south-western China. At that time, Kunming was a vital gateway to the outside world and a centre of learning. Universities and institutes from Beijing and Shanghai had moved there to escape the war. They formed China’s National Southwest Associated University, a unique combination of China’s top talent, comparable to merging Oxford and Cambridge in a mountain city under air raids.

In the university’s laboratories, Needham observed researchers extracting hematoxylin for cell staining from local plants, as imports had been halted due to the pandemic. Lacking microscope slides, they used pieces of glass cut from windows shattered by bombing. Physicist Zhao Zhongyao had even carried 50 milligrams of radium out of Japanese-occupied Beijing at great personal risk. With it, he conducted experiments on neutron-induced radioactivity. Needham called this the spirit of “doing what seems impossible.”

Building Bridges in a Time of War

Needham had planned to focus on the history of science. But after seeing such scenes, he felt that moral and material aid could not wait. Travelling to Chongqing, he wrote to the British Council, proposing the creation of the Sino-British Science Cooperation Office. London approved his idea quickly. He then compiled a list of urgent needs based on what he had observed.

Thanks to the “Hump”, an air route over the Himalayas flown by Allied pilots, much-needed supplies and scientific materials reached China. They included scientific books, journals, microfilms, and laboratory equipment. Chinese universities had lost most of their collections in the war. The 6,775 books sent and 167 British science and medical journals on microfilm that Needham brought himself were a lifeline.

During the war, Needham played a crucial role in rebuilding China’s connection to the global scientific community. He even encouraged Chinese scholars to submit their research to leading journals abroad. He helped send out 139 manuscripts, and 86% were accepted. These papers allowed the world to see China’s scientific achievements and laid the groundwork for postwar cooperation.

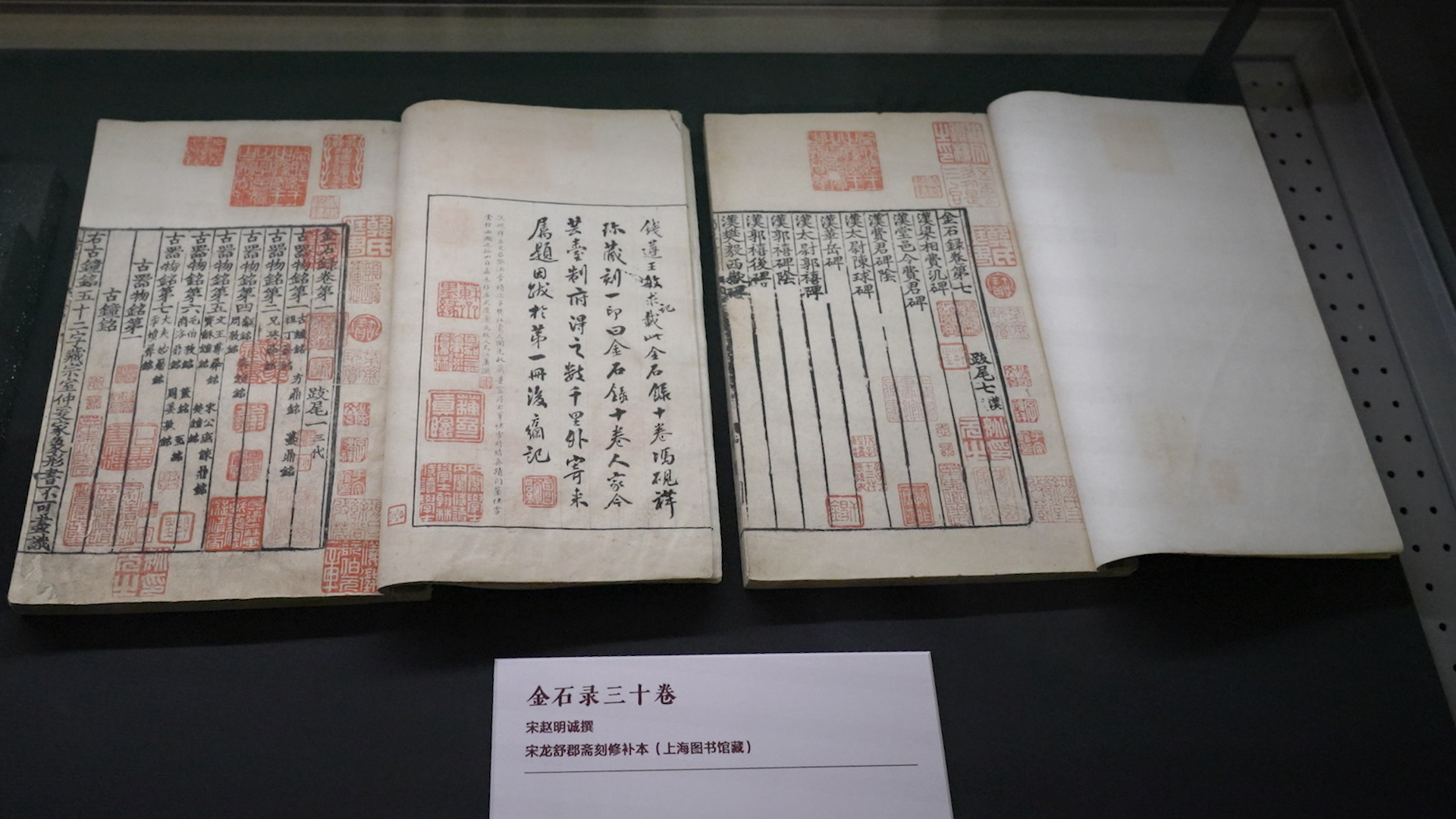

Liu Xiao notes that Needham’s wartime papers, diaries, reports, and letters reveal that he formed lasting friendships with Chinese scholars. Many later took key roles at UNESCO and other international organisations. For Needham, the experience also shaped the rest of his career. His monumental Science and Civilisation in China grew from the respect he developed during those years, and from his belief that the world should understand China’s scientific heritage and enduring spirit.

Reported by Zhixin Nie, edited by Chen Wang, additional reporting by CNS.

If you like this article, why not read: Beyond Borders: Dr. Assmy’s Century-Old Legacy in Chongqing