Professor Liu Xiao from the Department of History of Science and Technology of the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and a visiting scholar of the Needham Research Institute of Cambridge talks to East Meets West about some of Joseph Needham’s lesser known stories.

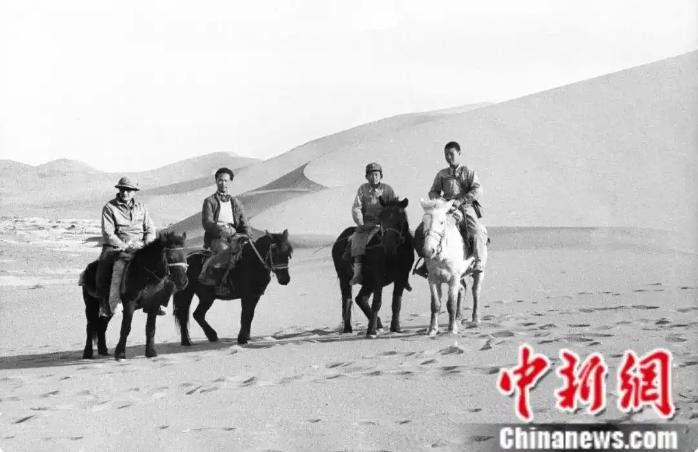

From 1943 to 1946, renowned British scientist Joseph Needham traveled to China, visiting more than 300 universities, research institutions, and industrial facilities. He witnessed how the Chinese people continued their academic and research efforts despite the risks of war.

In 1943, China was in the midst of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, why did British scientist Joseph Needham risk his life to come to war-torn China?

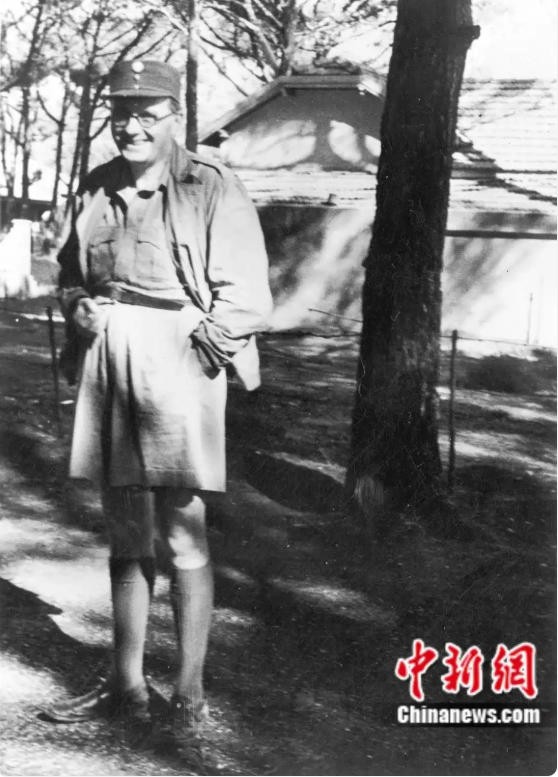

Joseph Needham arrived in Kunming in February 1943. His plan to come to China had been through a long period of work and preparation. The earliest contact could be traced back to 1939, when he met a Chinese student named Lu Guizhen. Through her, Needham came to understand China’s long and brilliant culture, sparking his interest in researching ancient Chinese science, technology, and society.

The total resistance against Japanese aggression began in 1937, and Lu Guizhen’s hometown, Nanjing suffered a massacre. Needham and his wife were deeply aware of the suffering endured by the Chinese people and had requested permission from the Chinese embassy to visit China. But at the critical point during the war, Needham was in fact unable to make the journey.

When the Pacific War broke out, the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) formally declared war on Japan, and UK has begun to place greater emphasis on its relationship with China, Needham was caught of the attention of high-level officials. Due to the neutrality of science and its significant value in warfare, its diplomatic role has become apparent. As a professor at Cambridge University and the Fellow of the Royal Society, Needham was formally granted diplomatic status and assumed wartime diplomatic duties.

Joseph Needham witnessed Chinese scientists conducting research under harsh conditions to contribute to the war effort. How did the wartime spirit of the Chinese people impress Needham?

Joseph Needham initially came to China with sympathy and a desire to help,but when he saw even in the face of extreme hardship, Chinese scientists and educators demonstrated a fierce will and high morale, his feelings shifted from sympathy to deep respect, and he became a committed supporter of the Chinese people.

Kunming served as a vital gateway to the outside world for China at that time, hosting numerous important institutions. Needham visited the Institute of Physics, National Academy of Peiping, which had relocated southward. He observed that the institute had fully shifted to wartime operations, establishing an optical factory to manufacture crystal oscillators for the Allied air forces. They cut circular discs from Mobil tinplate oil drums, hammered them into thin sheets, then spun them at high speed on pedal-operated machinery to cut crystal.

In the laboratories of the National Southwestern Associated University, Needham observed researchers extracted hematoxylin for staining cell nuclei from native Yunnan logwood when it could not be procured. He observed when microscope slides ran low, researchers used pieces of glass cut from windows shattered by the air raid instead. He also learned that Physicist Zhao Zhongyao risked his life to bring 50 milligrams of radium out of Tsinghua University in Peiping to conducted experiments on neutron-induced radioactivity. Needham called it the spirit of “doing what seems impossible”.

The “Central Epidemic Prevention Bureau” produced urgently needed serums and vaccines for the war effort and successfully developed penicillin. In Joseph Needham’s view, the story of the vaccine factory “is an epic in itself”. For him, the practice of reusing agar through special processing epitomized the tenacious spirit of the Epidemic Prevention Bureau.

Joseph Needham, who had originally intended to devote himself to the study of the history of science, “felt that the need for moral and material support was too urgent”. Therefore, once arriving in Chongqing, Needham submitted a report to the British Council proposing the establishment of a Sino-British Science Cooperation Office to carry out relief work in China. London approved his idea quickly. He then compiled a list of urgent needs based on what he had recorded during the inspection tour.

What did Joseph Needham do for science and education in China during wartime that earned him the title “a friend who sent charcoal in snowy weather” from Chinese people?

By the latter stages of the War of Resistance, the nascent scientific forces of ancient China were nearly on their last legs. Joseph Needham’s primary task was to boost morale and provide urgently needed assistance.

With London’s approval, Needham was authorized to use “the Hump” to transport urgently needed supplies for Chinese scientists. He was allocated sufficient space and tonnage on U.S. military transport aircraft bound for China. Supplies procured from Calcutta as Needham requested shall be delivered at least once a week, with transportation costs borne by the British government. Chinese universities in rear areas of the war were also benefited from British donations.

These supplies include scientific and technical books, journals, microfilm, and scientific instruments. Many universities and institutions scattered across remote rural areas had lost vast collections of books, making Joseph Needham’s donation of 6,775 books was like a timely relief. 167 British scientific and medical journals were delivered to China in the form of microfilm. The Science Cooperation Office provided emergency scientific equipment supplies to laboratories in China’s rear areas, processing 333 orders and making a tangible contribution to sustaining scientific research activities.

Needham reestablished scientific communication channels under wartime conditions. He published articles in Nature magazine, providing an overview of the scientific and technological landscape in different regions he visited during each trip. Chinese publications such as Science Communications were distributed or reprinted to the West. He also directly recommended Chinese research papers for submission to renowned international journals, submitting 139 manuscripts to Western publications with an acceptance rate of 86%.

He also provides consulting services to Chinese scientific and educational institutions. In Chongqing, his team delivered at least 100 presentations and conducted a total of 123 science lectures during their travels. Beyond academic content, these lectures also offered incisive recommendations on wartime scientific mobilization and strengthening international liaison.

After World War II, Joseph Needham advocated for “science for peace” and promoted international scientific cooperation. What impact did his visit to China have?

As Joseph Needham’s mission to China during wartime, promoting international scientific cooperation remained a top priority. He believes that this major war gave rise to a new form of organized international scientific liaison, namely the “Science Cooperation Offices”.

His first lecture in Kunming focused on international scientific cooperation, aiming to transfer the most advanced applied and pure sciences from highly industrialized Western nations to less industrialized Eastern countries. The Sino-British Science Cooperation Office was established in Chongqing, the rear base during the war, to assist Chinese scientists in conducting regular scientific activities and improving the backward state of industry. Following the war, in accordance with a resolution by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), science offices were established in multiple locations worldwide, all situated in less developed regions.

During his time in Chongqing, Joseph Needham formed a sincere friendship with Zhou Enlai from the Eighth Route Army Office and came to genuinely believe that China should follow the socialist path. During the journey to the north at the time of the victory in the War of Resistance, he had already contemplated traveling personally to Yan’an. Needham was regarded as a true friend of the Chinese people and became an important link between China and the West after 1949.

Your research on Joseph Needham and the history of science and technology in China during the War of Resistance spans both East and West. What new materials have you uncovered?

This research project combines Joseph Needham’s diaries and photographs to vividly present a comprehensive panorama of wartime science in China through both text and images, recorded in the book Chinese Wartime Science Through the Lens of Joseph Needham. From the collection of over 1,400 relevant photographs held by the Needham Research Institute in the UK, we have selected more than 800 images, many of which are being shown to the public for the first time.

By organizing and interpreting Joseph Needham’s primary wartime documents—including papers, diaries, reports, and correspondence—we have clarified several key issues, such as Needham’s official status and logistical support, while also correcting errors in his travel route to China.

From this, we see Joseph Needham’s gradual deepening understanding of Chinese science, technology, and culture. Through his interactions with Chinese scholars, he found like-minded friends whose support propelled his international scientific collaboration efforts—many of whom went on to serve at UNESCO after the war.

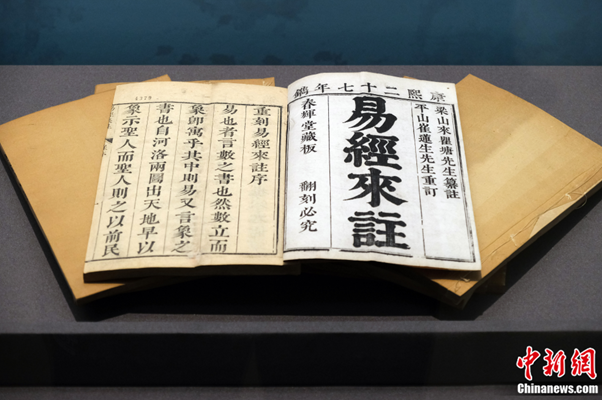

More people provided crucial assistance to Joseph Needham in writing his book, Science and Civilisation in China in a long period. In September 1982, Joseph Needham discussed plans to establish the East Asian Science Library during his visit to China. Within days, patriotic overseas Chinese donated £640,000. On October 23 of the same year, the State Science and Technology Awarding Meeting of the People’s Republic of China was held. Science and Civilisation in China was awarded the First Prize in Natural Sciences, making Needham the first foreigner to receive this honor.

If you liked this article, why not read: How Can We Not Overlook Overseas Chinese on the European Battlefield When Commemorating the Victory in the World Anti-Fascist War?