From the southern edge of Yotkan Town in Hotan, Xinjiang, visitors heading west immediately notice the colourful, “flowing rainbow” of Atlas silk storefronts. The bright patterns seem to leap off the walls, and as a result, they instantly capture attention.

“It’s simply dazzling!” said Wei Yihan, a student from Hotan No.1 Primary School, dressed in a traditional mamian skirt. As she explored the intangible cultural heritage (ICH) market, she not only admired the stalls but also discovered many “must-have heritage treasures.” She added, “I hope I can wear a mamian skirt with Atlas silk patterns one day.”

Recently, the “Xinjiang Is a Great Place” ICH aid-to-Xinjiang exhibition was held at Yotkan Ancient City. The event not only featured 435 representative ICH projects but also showcased 383 inheritors. Moreover, participants came from Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, as well as 25 other provinces, regions, and municipalities.

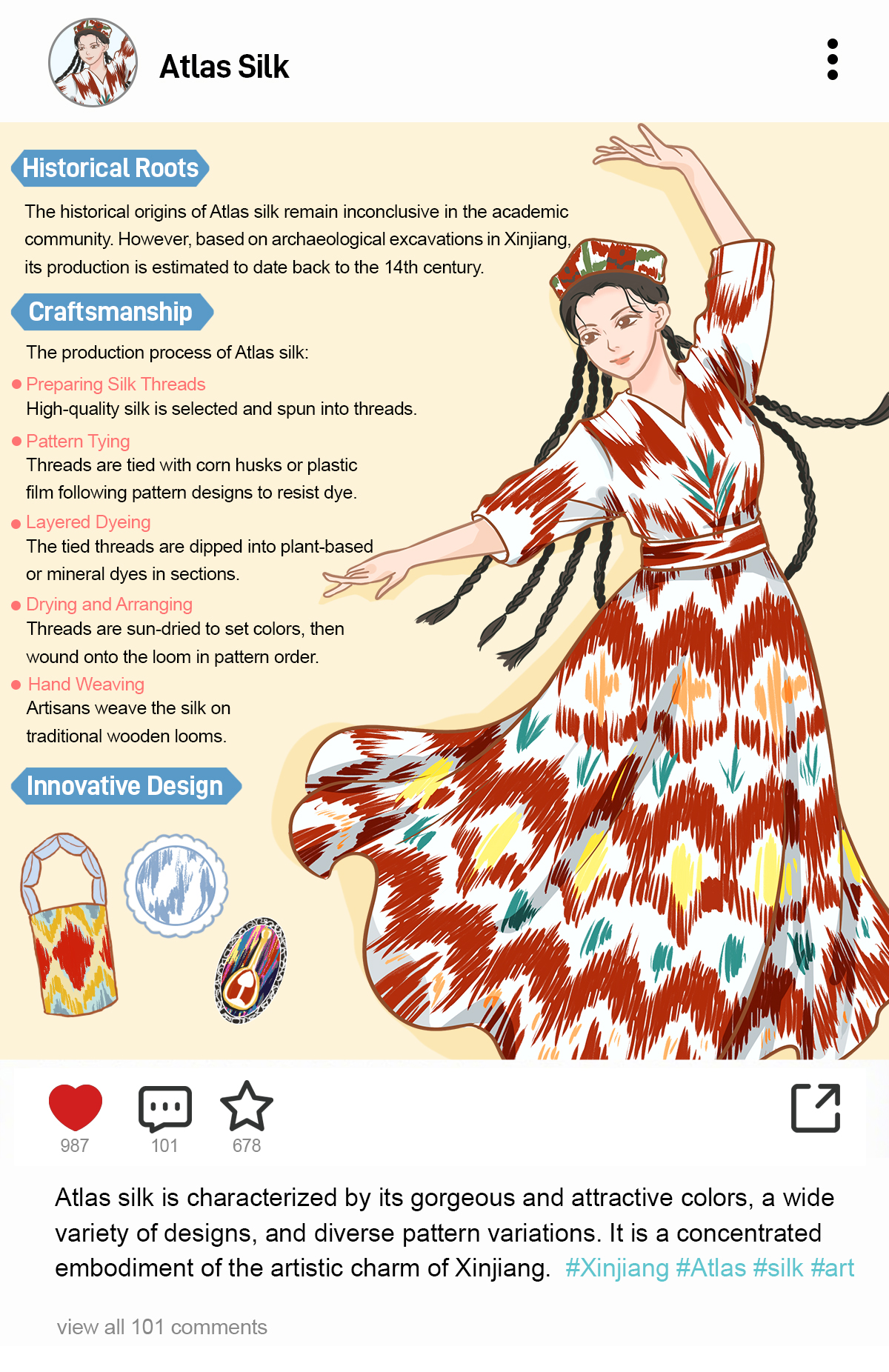

Atlas silk, which is woven and dyed by Xinjiang Uyghur artisans, is recognised as China’s national intangible cultural heritage. It displays bright colours, elegant designs, and a wide variety of patterns. Furthermore, it highlights the artistic charm of Xinjiang in a concentrated form.

Atlas silk also has a long history. Importantly, local craftsmen source raw materials mainly from abundant mulberry trees and silkworms. In addition, they rely on exquisite techniques and endless creativity. Consequently, every Atlas silk pattern remains unique.

Even today, artisans still follow traditional steps to produce Atlas silk. Therefore, every thread reflects the Uyghur people’s deep understanding of beauty. Historically, craftspeople first developed Atlas silk in the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties. Then, artisans in Hotan and Kashgar absorbed Central China’s silk techniques. Afterwards, however, they innovated their own distinctive methods.

Tie-dyeing forms the key step in colouring Atlas silk. Interestingly, Xinjiang artisans use a different approach from Central China. While Central Chinese artisans dye silk after weaving, Xinjiang craftspeople, by contrast, dye the silk first and weave it later. They carefully lay out warp threads, arrange colours, and tie them with precision. Next, they dye layer by layer before weaving. As a result, this method blends colours naturally. Consequently, patterns form soft halos, and overlapping hues create a rich, layered effect.

Written by Yi Shen, poster designed by Di Wang.

If you like this article, why not read:【Trending Code】Pulu Reborn: How Tibetan Weaving Found New Life in Paris